Hobonichi Techo User Interview - A “History of the World” According to Me - Tamaki’s Techo

Every year we survey techo users about the Hobonichi Techo and how they use it. In our 2019 survey we received a curious submission from a user who told us about how they’d made their techo into “a history of the world collected into a single book.” A history of the world? In a techo? We talked to this user, Tamaki, and included her answers in the Hobonichi Techo 2020 Official Guidebook.

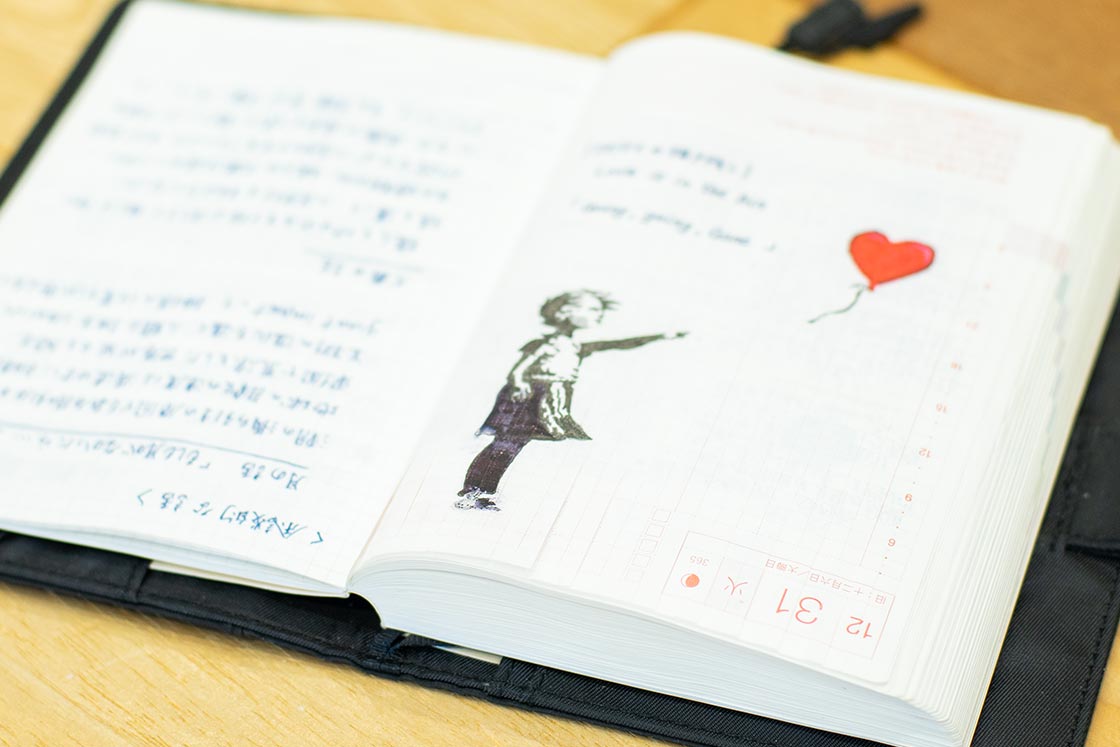

We received another email from Tamaki this year that said, “I wrote in that techo—the one you featured—all the way up to New Year’s Eve, and I must say, it has really turned into something amazing.” We asked Tamaki to give us an update on the techo that crammed 4.6 billion years of history into a single book.

——It’s nice to talk to you again. The goal you set for your 2019 techo was a real marathon, but I see you finished!

TamakiI sure did!

You can see all pages of Tamaki's techo on her Instagram.

——Could you tell us once again what made you choose to turn a Hobonichi Techo into a history book?

TamakiSure. I work in technology, and I had started to feel overwhelmed by how rapidly things were evolving around us, when I’m already inundated with information every day. I started feeling uncertain about the future, so I found myself wanting to learn more about the path humans have taken to reach where we are today, kind of as a way to ease my mind.

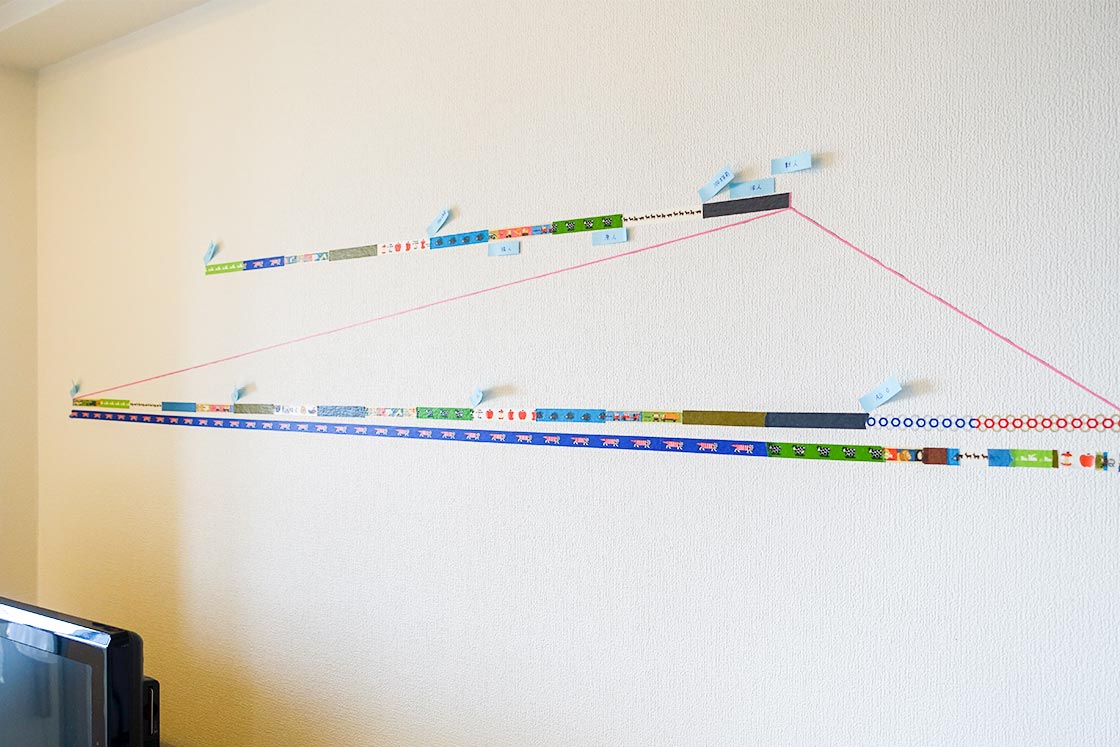

Looking back, even though I enjoyed history when I was a student, there was a lot I didn’t know, like what kind of place Japan was when ancient Egypt was flourishing. So I took a big long piece of washi tape and stuck it up on my wall at home.

——And that’s the “Wall of Inspiration” you told us about in your Hobonichi Techo survey.

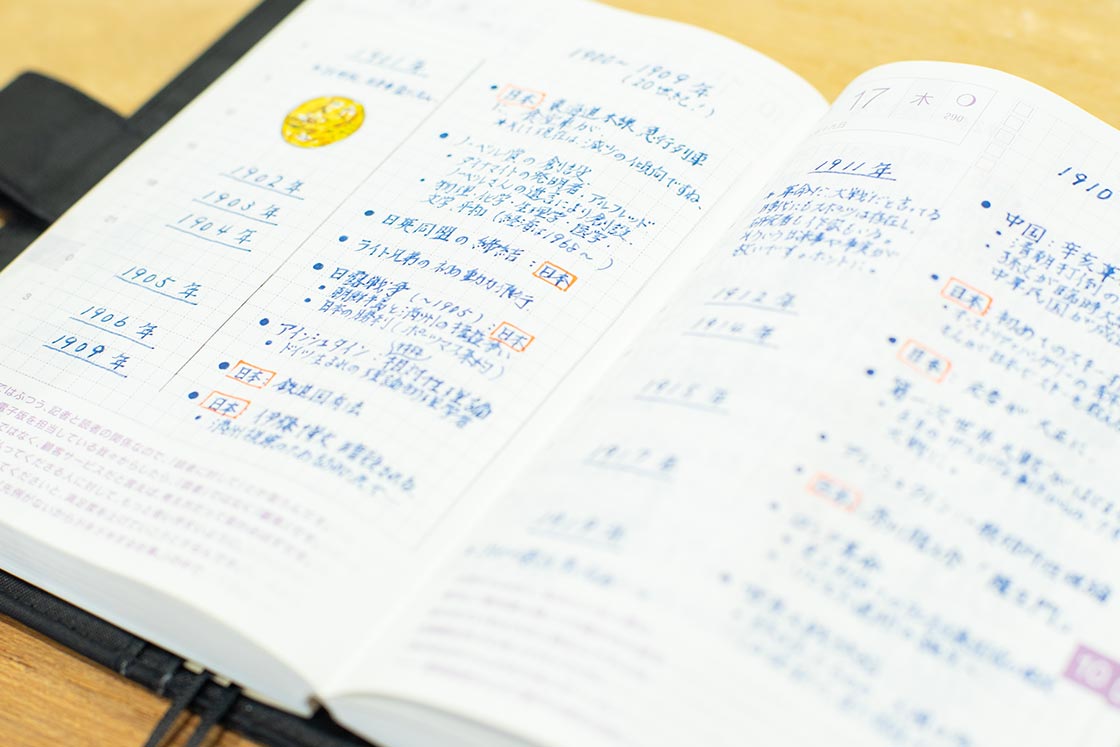

TamakiRight. It’s a visual representation of Japan’s eras lined up against the western calendar. Once I set this up I made all kinds of discoveries, and realized just how little I’d understood about history. That’s when I decided to make a timeline of my own.

——Why did you choose the Hobonichi Techo for your timeline, rather than a standard notebook?

TamakiI considered several options—a notebook, an Excel spreadsheet, or even a really long scroll I could roll up. But none of them sounded like something I’d want to keep up with. That’s when I remembered the Hobonichi Techo I’d used a few years back to track my task lists at work. I was familiar with the book, and I’d have an entire year’s worth of scheduling set up for me when I was filling it out! So I went out that same day and bought one.

——So you’d have a schedule already set up for yourself?

TamakiExactly. It was 2018, the year before I started, and in order for me to write out all of history in a year, I could just assign from which until which year would be represented on each of the daily pages.

——And that’s how you pulled it off. Amazing.

TamakiI’ve never really done anything so consistently, in such a planned way. That’s why I made sure to be as prepared as I could, to make it easy for me to keep up with it. On the header page, I set down my motive for creating the timeline, so I could look back on that whenever I needed to. I also allotted all the days I’d be writing out the timeline, and gave myself “rest days” where I wouldn’t have to do anything.

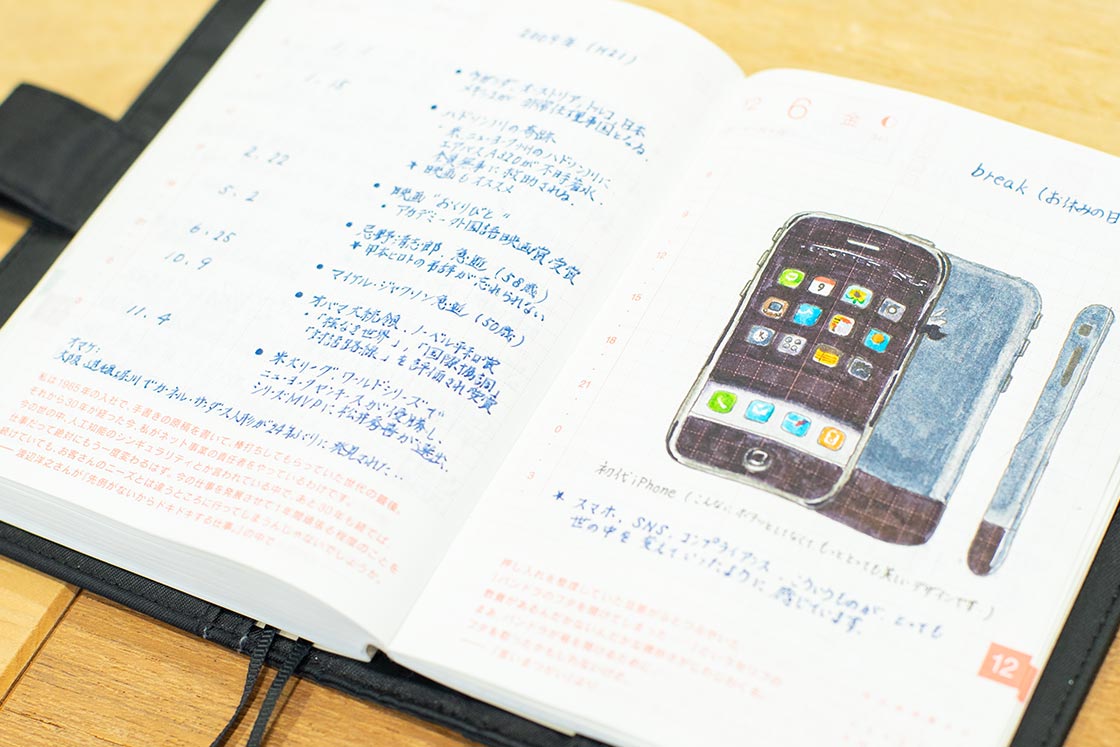

——Looking at your finished book, I see you’ve got some really detailed drawings in your days off. (Laughs)

TamakiHalfway through the project I got the motivation to draw things whenever I reached a page I’d set aside for an off day.

——Did you have a certain time picked out each day that you would write in the techo?

TamakiI usually wrote after work, some time between 10 PM and midnight. I had a list of bookmarks for some reliable websites, so I’d browse through those, pick out a book one of them mentioned, and read through it to find the information that really stood out to me. That’s how I picked out my timeline, but in May I actually started attending a class through the Hobonichi School, when there was a course on Darwin.

——So you spent the year pretty tightly connected to us.

TamakiYeah. I got home so late on the days I had class that it was too hard to write anything in the timeline—and besides, my head was already full from all the information I’d just taken in. I couldn’t just snap my fingers and go from Darwin all the way back to the Kamakura Period! (Laughs) So for those days I’d either write that day’s entry beforehand, or after I woke up the next morning.

——Hearing you talk about your process, and seeing this book right in front of us, I can’t believe you could possibly be the kind of person who has a hard time seeing things through.

TamakiOh, I was terrible. But just a month into this timeline project, the “uncertain future” that was my initial motivation? I didn’t even feel that any more.

——That change took a month... so according to this book, you got from the origin of the planet up to the Neolithic Revolution.

TamakiAs I spent my nights writing about all the dynamic changes the earth went through, I began to think, “Well, things will happen, but it’s nothing to worry about.” So about a month in I actually thought about quitting.

——That’s so soon!

TamakiBut I’d worked so hard to get that far, so I thought, I’m never going to keep up with something like this again—I might as well try to get a little farther. I just cycled through that thought process over and over until I reached the end.

——Did you hit any slumps along the way?

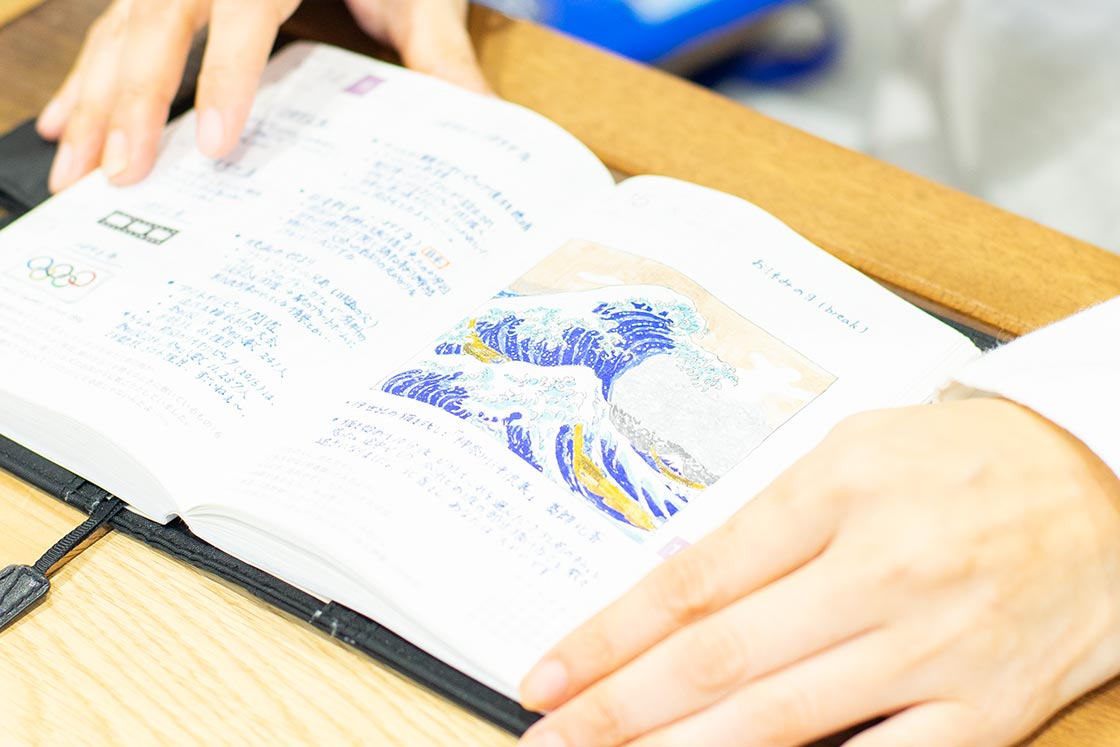

TamakiLots. I drew this in October.

——Wow, what a drawing! So this page was one of your days off.

TamakiYeah. And even though I drew out the whole Great Wave off Kanagawa, I had a fever that day. (Laughs)

——That’s quite a detailed drawing for someone to make with a fever.

Tamaki:

I thought it was pretty crazy of me to do, but when I finished drawing it I felt really accomplished.

——I would hope you did after drawing something so beautifully!

TamakiI was basically an empty shell by the end of it. (Laughs) I was able to keep going with the project, but two weeks after that I got another fever, and then I finally rested without writing anything. I took about three days off.

——How did you get back into it after that?

TamakiI was posting daily updates with my techo pages on my Instagram. I didn’t have a ton of followers, but when I said I was going to take a break because I’d caught a cold, several people sent me messages asking if I was okay.

——Ah, your readers.

TamakiI didn’t think I had any, but when they told me they looked forward to seeing my pages again, I felt like I just had to continue.

——It’s a good thing you were on Instagram, then! Once you were past October, it had to be in the bag, right?

TamakiNo. At the very end, something else happened: the Frixion Incident.

——Frixion... Don’t tell me...

TamakiMy entries disappeared.

——No way, right at the end?

TamakiI was going to go home to see my family on December 28, but that morning I thought, “It’s too much of a pain to bring this many pens all the way home.” So I filled in all the rest of the entries for the year.

When I finished this drawing, I wanted to dry the wet ink faster. I’d never tried it before, but I had the bright idea of using a hairdryer to dry the ink. Then... you know the rest. (Laughs)

——How much disappeared?

TamakiUp until December 10th. Luckily I had taken pictures of all of them to post on Instagram, so I was able to rewrite it all. I color in my drawings with a different kind of pen, so I basically just had to write all the text.

——That’s still an incredible amount of labor! Even though you had that incident right at the end, did you feel like anything had changed as a result of your year-long project?

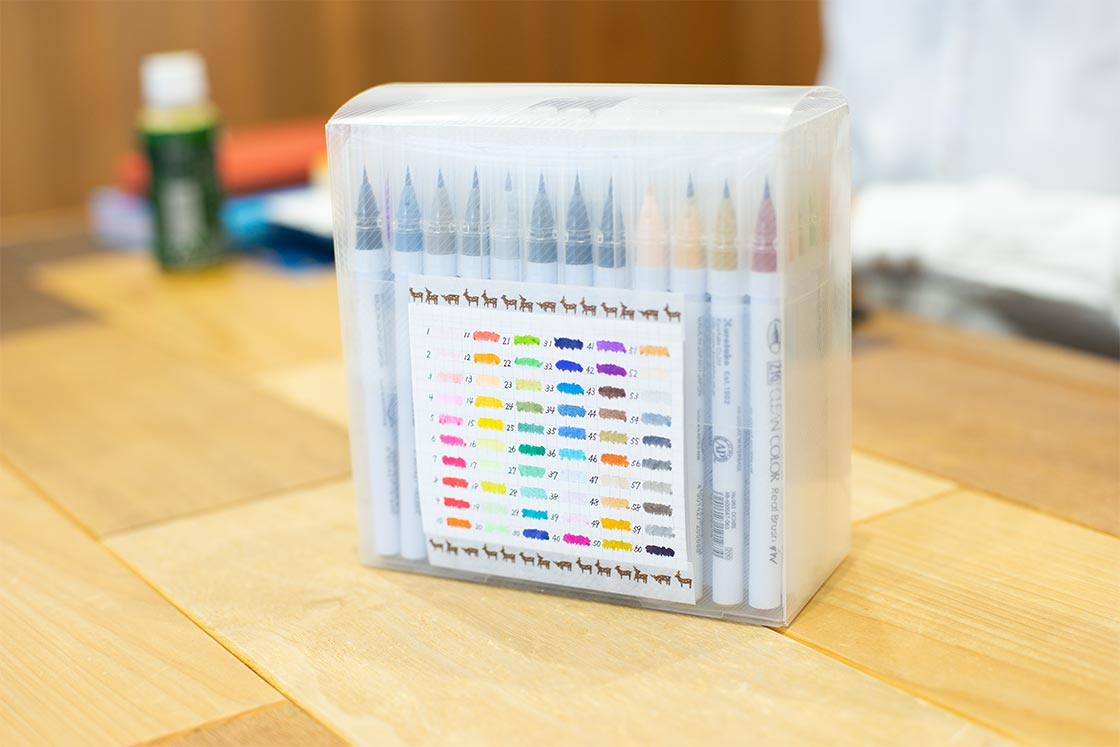

TamakiI think my handwriting and drawing improved a little bit. I was impressed that, after keeping on it for a year, my handwriting became legible. My drawing skills especially surprised me, because I never really drew before this, and I never dreamed I’d ever be drawing this much. I ended up buying so many pens.

As I wrote the timeline, I also thought a lot about all the ordinary people who didn’t make it into history books. A lot of the information about the Heian Period focuses on the elaborate lifestyles of the nobility. But that dazzling image is clouded when you read about how average people lived in rather filthy conditions and had short life spans. Then you’ve got the Sengoku Period—the Age of Warring States—and the only people you read about are army generals, when the unrelated people who got roped into that mess must have had it really hard. I often wondered what those people thought and felt in their daily lives, living in times like that. It made me realize that was the reason I enjoy Rakugo so much.

——So the way you collected all those stories by hand helped you realize some things about the rest of your life.

TamakiI did. I think I just wanted to use the techo to create a curation of my own. It’s impossible to fit ten or a hundred years into a single page, so I had to make choices about what to select from the endless historical information already out there. I made sure to include the major events, but aside from that it was just me discovering what I was personally interested in.

——When we talked to you last year, you told us you weren’t sure what you’d write in 2020. What have you ended up writing about?

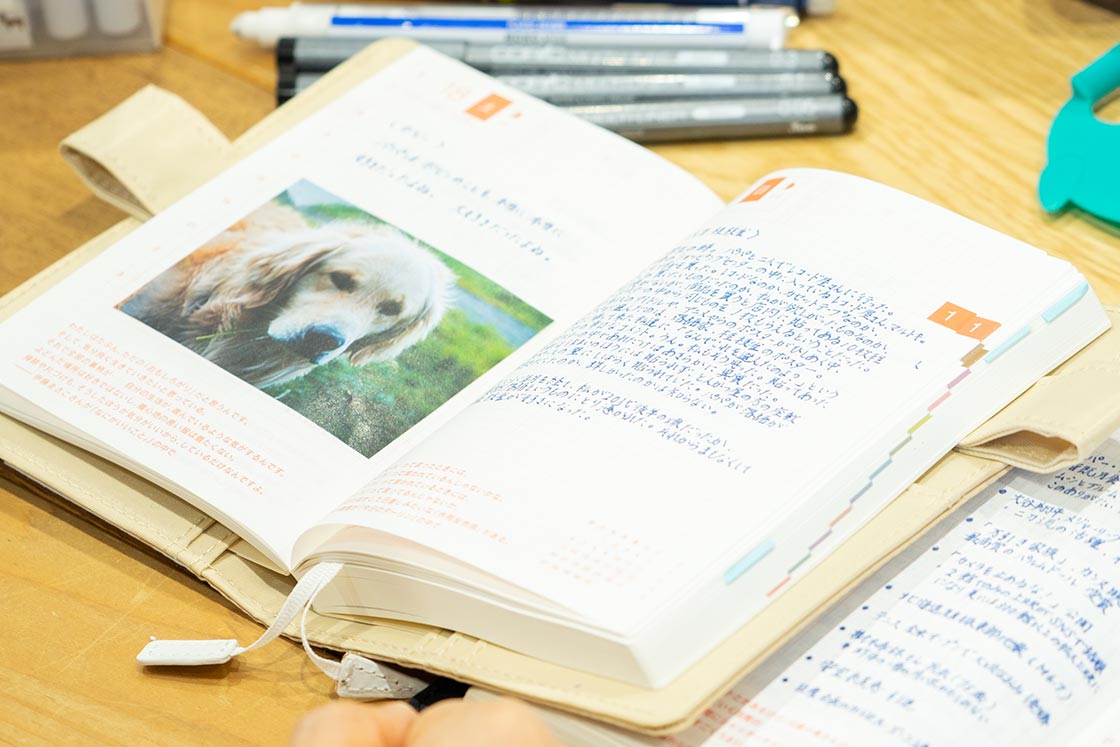

TamakiMy father, who passed away last year. Every day I write down a memory.

——From the history of the world to memories of your father. What an intimate thing the techo has become.

TamakiLast year I took notes on things that had happened, so this year I wanted to write something in my own words.

——Wow, just being able to see a tiny portion of it brings tears to my eyes. Of course, this was also true of the historical timeline, but I’ve never seen a techo used this way before. It’s going to become something really special.

TamakiThis year’s project feels even more rash to try than last year’s. It’s hard enough to remember anything with my mother, but it’s even harder to remember things that happened with my father. But if I were to ever do it, this is the year. Though, this might also be the year that I’m not able to make it to the end. (Laughs)