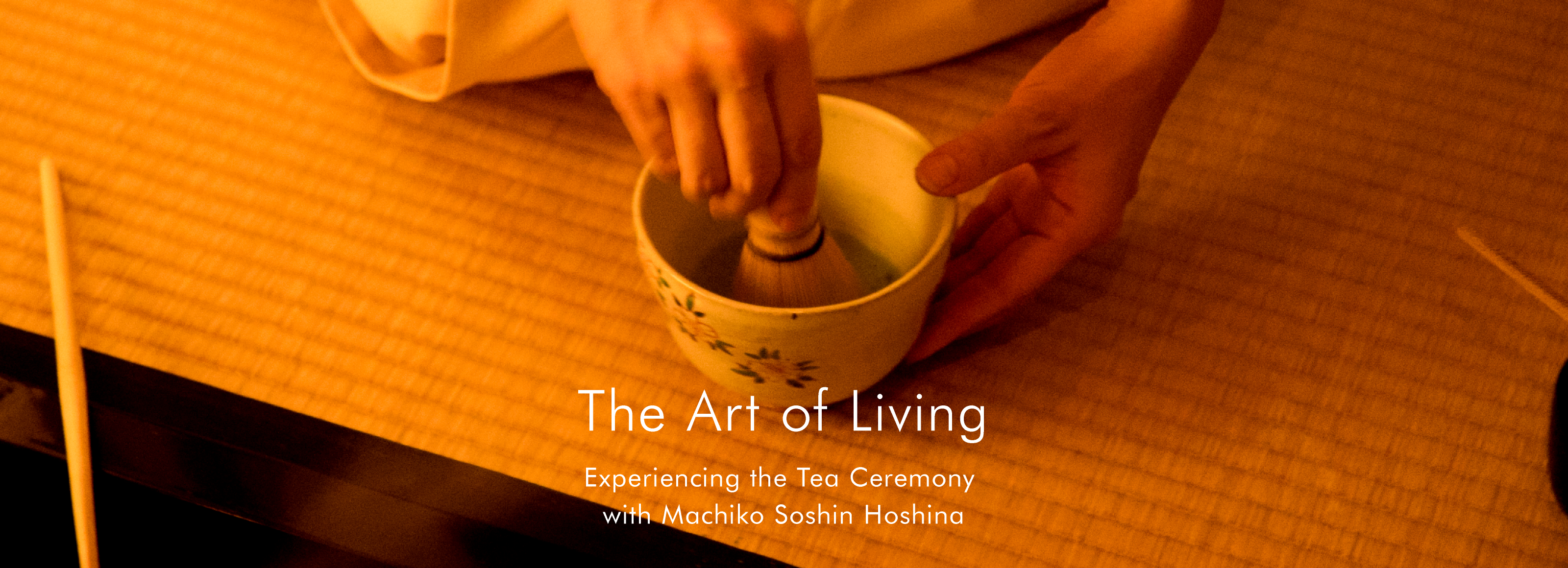

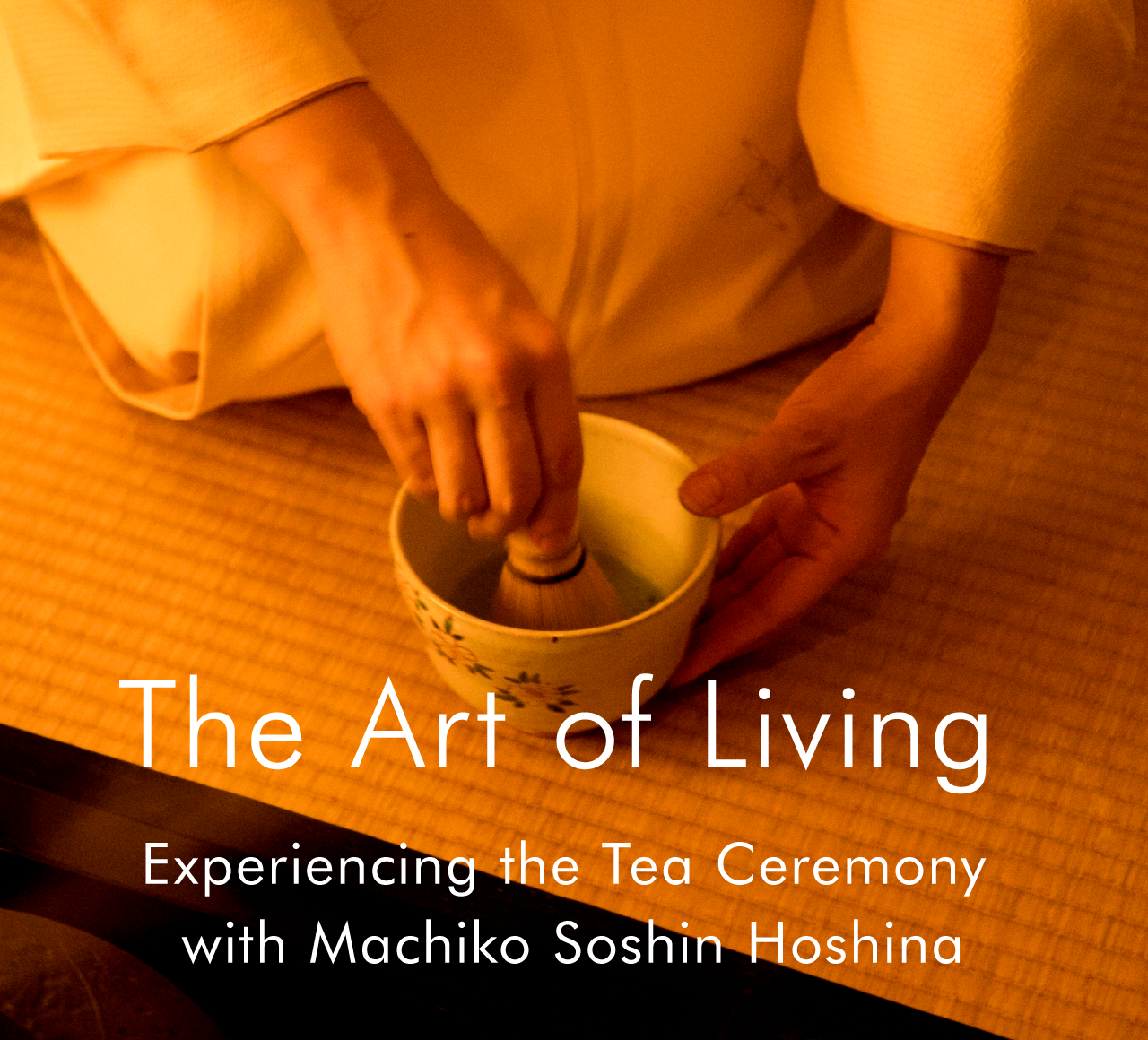

When tea practitioner Machiko Soshin Hoshina consulted on our 2017 Guide to Japanese Tea, she told us so much more about the tea ceremony than we were able to cover on that one page. We decided to catch up with her again, and this time present a full story on the tradition for our online readers. In the short time we spent together Hoshina showed us how a centuries-old ritual and its etiquette are kept very much alive today, and how she shares her knowledge and the Japanese art of living with visitors from abroad.

Our gathering was in November, just after the robiraki ceremony that marks the shift from use of the summertime furo brazier to the sunken hearth. In the tea world, the hearth you see in these photos is used until April.

A descendent of the Tokugawa family and a tea practitioner of the Urasenke style, Machiko Soshin Hoshina conducts tea ceremonies and classes for all ages in English and Japanese at embassies, companies, and schools in Tokyo. For more information or to book an appointment, visit her website: tranquilitea.jp

- Hoshina

- Sen no Rikyu perfected Chado, the Way of Tea known as Chanoyu or tea ceremony in Japan 450 years ago, but the history of drinking tea dates back earlier to the eighth century when Japan had the first cultural contact with Tang dynasty China. In the twelfth century Buddhist monks brought back tea seeds and utensils from China and the custom of drinking matcha powdered green tea developed in Zen temples. In the fifteenth century Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa held art-centered, contemplative tea gatherings as an antidote to times of unrest. So you can see that historically, tea, faith and art have been intertwined in sophisticated ways.

In the tea ceremony, each of the five elements representing the universe — wood (charcoal), fire, earth (pottery), metal (kettle), water — are essential. All of these energies come together to prepare the perfect bowl of tea and celebrate the union between a host and her guests.

When you think about what hosting a tea gathering entailed all those centuries ago — chopping wood, drawing water, preparing a fire — you can understand, and really appreciate, why so much symbolism is built in to the ritual. Preparing and serving a bowl of tea for someone is a time-honored act of hospitality. Today, as then, when done mindfully it can be an offering of serenity, an oasis. A gift of time spent together that’s removed from all the doings of the material world.

- Hobonichi

- To the uninitiated, it can seem so formal — daunting, even.

- Hoshina

- It’s easy to feel anxious about the protocol and etiquette but really, underlying it all is just this simple idea of people gathering to create and enjoy some moments of tranquility together.

- Hobonichi

- What do first-time visitors need to bring?

- Hoshina

- It’s a good idea to wear clothing made of soft stretchable fabric, and skirts that cover the knees, as you’ll be kneeling on tatami mats. The only thing we ask people to bring is a pair of clean white socks — kimono tabi socks are best, but even regular socks will do.

- Hobonichi

- Why is that?

- Hoshina

- The tea room is considered a sacred place. And tatami mats are made with rice straw at their core, so we wear clean white socks or tabi for purity and out of respect.

We also ask guests to take off their accessories. In the past, samurai had to remove their swords and enter the tea room as equals. Today, the symbols of our social status are wristwatches, jewelry, cell phones. So you should set those aside before entering. This is also to prevent scratching of, or damage to, the utensils you’ll be handling.

- Hobonichi

- For those who have never experienced the tea ceremony before, can you walk us through the steps?

- Hoshina

- Of course! Today I will demonstrate chaji, the formal tea gathering performed today much as it was 450 years ago. It begins with the laying of the charcoal and proceeds to the serving of a meal and the climactic koicha thick tea, then concludes with a serving of usucha thin tea. As this full course takes more than four hours, most visitors today experience a simplified version known as chakai, where only usucha is served. I’ll show you the larger context from which that comes.

First, before entering the tea room guests purify their hands at the stone basin. At a formal tea house, this would be located in the roji garden. Since we live in an apartment building, ours is outside on the balcony. In either case, the well-kept refreshing garden signifies the world of Zen. It serves as a boundary between the outside world of mundane affairs and the inner, sacred realm of the tea room.

- Hobonichi

- It’s a lovely garden!

- Hoshina

- We have some 50 varieties of plants here. It’s nothing like the roji garden path you’ll walk along as you approach a tea house but still, it’s an opportunity to appreciate the season and its expression, whether in the color of the leaves, the appearance of new growth, or something in bloom. The chabana floral arrangement we prepare for each ceremony comes right from here too. It’s the only living adornment you’ll find in the tea room. Typically a bud is used, to signify new or unfolding life. Sometimes we might arrange that with a colored leaf to symbolize aging — together representing the full life cycle.

- Hobonichi

- That sounds very Zen.

- Hoshina

- That’s right — in the tea ceremony Zen is always there in the background!

- Hobonichi

- So we wash our hands here?

- Hoshina

- Yes. It’s similar to the ritual you see at shrines. You take the ladle in your right hand, scoop water from the stone basin to purify your left hand, and then repeat vice-versa. Finally you pour water into your left hand to rinse your mouth.

Heart-to-heart communication and art appreciation

- Hoshina

- Before we enter the tea room, let me explain briefly what the tea ceremony is all about. Essentially it fulfills two purposes. The first is heart-to-heart communication between host and guest. The second is art appreciation. When you go to a museum, often the exhibits are behind glass. But in the tea room, you may handle the utensils, drink from the tea bowl, ask questions. I like to think of the tea ceremony as a kind of portal into other aspects of Japanese culture. Because it was perfected relatively late compared to other traditional art forms, it incorporates all of them — calligraphy, ikebana, incense, lacquerware, bamboo craft, ironwork, pottery, Japanese cuisine, kimono, architecture and garden design, classical literature, waka poetry and even elements of Noh. The tea ceremony really is a composite art.

- Hoshina

- It’s also like a time machine. Through the rituals and some of the treasured vessels that are used, you can imagine yourself back in 16th-century Japan, when samurai like Toyotomi Hideyoshi or Tokugawa Ieyasu and tea master Sen no Rikyu were alive. Also you see how contemporary Japanese people communicate and what we cherish. So it offers something very old yet also still alive and even new.

- Hobonichi

- You yourself are proof that the practice is very much alive today, and followed even in the home!

- Hoshina

- Because our family traces back to samurai lineage, we have tea utensils and implements passed down from our ancestors. While life is limited for any one of us, I often feel that such works, handled with proper care and carried down through the generations, enable us to feel the presence of the artisan who created them. You can hold a chawan bowl or lift the kama kettle and feel how the craftsperson put his effort or spirit into the piece. So this is another kind of inspiration we receive from the tea ceremony that is very special.

- Hoshina

- I like to recommend that visitors to Japan begin and end their trip with tea. In the short span of time it takes just to have a bowl of tea and a sweet, you can experience so many aspects of Japanese culture. Then, throughout your travels — in the people you meet, or the foods you eat and the ways in which the dishes are prepared, you’ll recall having had a glimpse of something similar in the tea ceremony. At the end of your trip, a tea ceremony can be a way to reflect on all those experiences — not only the traditional aspects, but also the ways in which people communicate.

- Hobonichi

- What do you mean?

- Hoshina

- For example, eye contact here in Japan is different, less direct than in other countries. If you are used to primarily verbal communication your experience of the tea ceremony might feel a bit lonely. But in fact there are many messages to pick up on. You may hear the sound of the simmering kettle, or of the bamboo whisk. You may notice the sound of my tabi on the tatami or the rustling of my kimono as I walk. Or the pouring of the water. All of these are rich in communication. Even the scent of the tea room is part of the warm welcome you can experience. For the Japanese, such non-verbal communication is very much alive in our interactions. If you are not used to this, upon first impression you might find us a bit cold, a little shy, perhaps. But when you slow down to the pace of the tea ceremony, you will see that you can’t judge warmth or sincerity by eye contact or conversation alone.

- Hobonichi

- So the ceremony is like a kind of meditation, an opportunity to use all five senses?

- Hoshina

- Yes, we speak of tea practice as being a kind of meditation in motion. Mindfulness is very important. During a ceremony, as active recipients of the host’s preparations and offerings, guests help to create the mood of ichigo ichie together. This is a teaching of Sen no Rikyu. It means that this meeting, this moment in time, will never be repeated and so should be cherished.