The Hobonichi Techo is a LIFE BOOK.

“The only one who can truly complete a Hobonichi Techo is the person using it,” says the creator of the Hobonichi Techo, Shigesato Itoi.

We want to provide a functional, easy-to-use planner that also serves as a place for users to capture all aspects of their LIFE (lifestyle, lifespan, living life) in every page. And with that hope, we are happy to share information on the Hobonichi Techo page about how easy the book is to use, ideas for customizing it to use in your own unique way, and how to make the LIFE BOOK truly a part of your life.

We would now like to share with you a very special article that was first featured on the Hobonichi website in 2013.

Feel the emotions from a century ago.

Hobonichi received an e-mail from a reader about a collection of vintage planners. The attached pictures were simply fascinating, not only the team from Hobonichi Techo but everyone who saw them, were deeply moved.

The daily planners belonged to a lady who lived 100 years ago in England. The reader (nickname Fiddlemum) wrote, “When I read these notes, they reminded me of the Hobonichi Techo.” We invite you to read along as we introduce these historical planners.

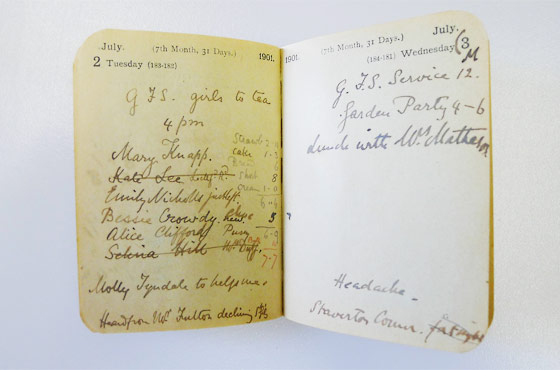

The woman who owned these planners was the wife of an Oxford scholar and lived in England over a hundred years ago. While there are three books missing, and the daily pages aren't filled in every day, her planners span from 1901 to 1918 and contain shopping lists and accounting notes on Mondays, entries about her son coming home from the boarding school, time tables for the train returning him to school, entries about enjoying tea or playing chess with someone, and other matter-of-fact writings. While she never writes her personal thoughts or feelings, based on the frequency of tea parties and dinners, we can see she lived an elegant life.

For example, in 1901 she hosts a tea party on July 2nd, attends a garden party on July 3rd, and perhaps because of her consecutive parties, at the end of the day, she notes, “Headache.”

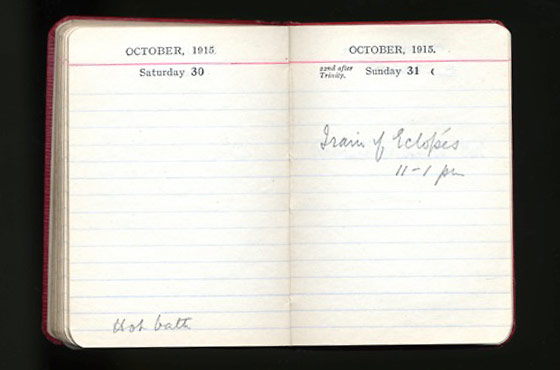

In the summer of 1915, she loses her son to the war. On August 30th, she writes about a telegram she received from the War Office at 2:15 PM. After that, there is an extended period of blank pages. And when her weekly Monday shopping list disappears, the brief entry saying someone stopped by has us wonder whether she had them run her errands. In these ways, the empty pages speak volumes. In October of that year, she left to volunteer at the Red Cross in France—while we assume she was an intelligent, well-brought up woman to begin with, perhaps she was moved to join the service by her son’s death. And on October 30th, there’s a note that says Hot Bath. Looks like the English 100 years ago enjoyed a nice hot bath as much as the Japanese—enough to record it for posterity.

Fiddlemom also wrote in her e-mail, “There’s a lot a planner can say about a person, even through offhand notes and blank pages. Reading through it, you can feel the history and the person’s personality. How fascinating it would be to find someone’s Hobonichi Techo a hundred years from now from another country and look at all the scribbled notes. I’m sure that book would strike a chord in the reader in the same way.”

Just as we can witness the life of a woman in England a century ago, perhaps our own notebooks will do the same for a stranger who finds our book a hundred years from now. Even if the notebook contains nothing more than a collection of quick, offhand notes, it leaves behind something that trancends time and space to tell the story of your life. That great potential is hidden in its pages.