1The feel of hand-spun, hand-woven fabric.

Iwate Home Spun

In Hanamaki city, Iwate prefecture, a small company called Nihon Home Spun thrives at the foot of the Kitakami Mountains. With fewer than 20 employees, Nihon Home Spun produces fabric sought after by brands from around the world. Their woolen Home Spun fabric exhibits all the particular tactile and visual qualities of hand-spun and hand-woven textiles.

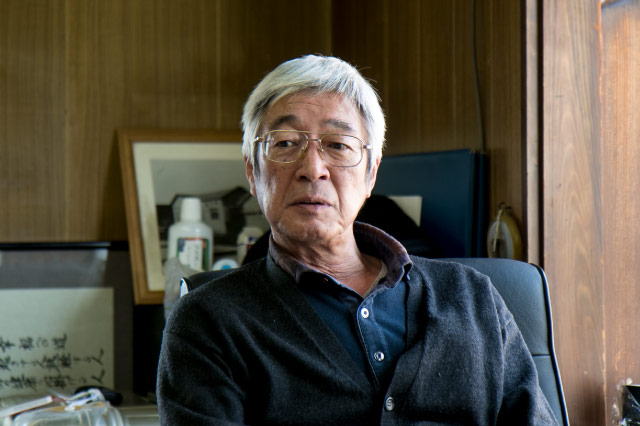

The company carries out every step of the production process itself, from the dyeing of sheep’s wool to the completion of the finished textile. We talked about the creation of Home Spun with company president Kanji Kikuchi.

Nihon Home Spun president Kanji Kikuchi.

- ――

- Thanks for meeting us today. We looked into the history of Home Spun and saw that this type of fabric was first brought to Iwate in the Meiji Period (1868 - 1912).

- Kikuchi

- Technically speaking, it was the sheep that were brought here first.

- ――

- Sheep?

- Kikuchi

- The Meiji period was characterized by a push for modernization, including a change in fashion from Japanese to western clothing. Silk, cotton, and linen kimonos were replaced by woolen clothes from the West, beginning with military dress and uniforms for civil servants.

- ――

- Why did those sheep end up in Iwate?

- Kikuchi

-

At first they were raised in Chiba, but sheep don’t do well in humid climates, so the ranchers elected to move the sheep to a drier place. That left a few options: Hokkaido, which has no rainy season; the Kitakami Mountains in Iwate; Nagano; and around the Abukuma Mountains in Fukushima. (In Iwate the humidity is low until you cross the mountains toward the Sea of Japan.)

So those four places were designated as the new homes for the sheep farms.

- ――

- Raising sheep seems very difficult.

- Kikuchi

- It is. Of the four places that were chosen, the area around the Kitakami Mountains had no major preexisting industries, so each farm in the area raised two or three sheep.

But during the First World War, imports into Japan stopped, including food. The focus turned to sheep as a source of food, which led the government to push harder for farmers to raise sheep. That’s about when techniques for creating homespun textiles were introduced to Japan from England.

By the Taisho period sheep’s wool was a source of income, so it was to everyone’s advantage to raise sheep.

- ――

- And that was the start of Home Spun.

- Kikuchi

-

The name Home Spun comes from exactly that homespun textile tradition. Today we still call something Home Spun if it’s machine-woven in a way that gives it a hand-woven feel, but at first the sheep’s wool was shorn and spun into threads at home. Every step of the process was done at home then.

It started when a missionary from Scotland came to northern Iwate and taught the locals there about homespun fabric. The most talented of his students was Otoko Umehara, who eventually assumed the role of teacher herself. The technique for making homespun fabric spread throughout the area. It was important that it did, because the missionary wasn’t going to be in Japan forever. (laughs)

Later, a government worker from Iwate went to Scotland and brought back a complete set of tools for local carpenters to reverse-engineer and replicate. The machines they made back then are still around today.

- ――

- Wow — that’s a century in use.

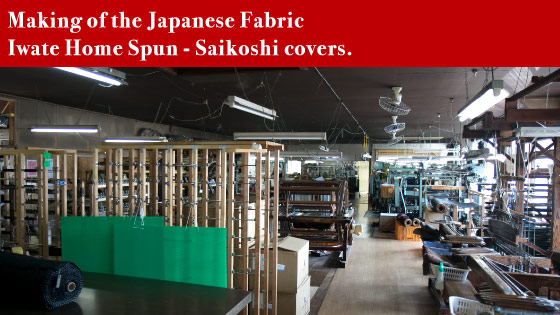

Kanji’s son Hisanori, who also works for Nihon Home Spun, showed us around the factory. The company uses refurbished looms from the Showa period (1926 - 1989). “Because they’re made of wood, of course, they deteriorate over time,” Hisanori told us. “But they’re not complicated, so if we take a part to a wood-worker, he can make one just like it.”

- Kikuchi

- Eventually every farm made homespun fabric, and the department stores would come here to buy it. They would make the fabric into coats and jackets. That continued into the Showa period, but when the Second World War came, everything changed. Wool was an important military asset, and the public was told not to use it. That caused homespun production to die out.

- ――

- Ah...

- Kikuchi

- When the war ended, my father was one of the men who came back from the front lines. He was out of a job, and there was no work. But the warehouse in town was still storing sheep’s wool that had been procured by the military, so he decided to start a company to produce the homespun fabric that everyone had, until recently, been making at home. He formed a partnership with the son of Otoko Umehara, bought the wool, and began to produce the fabric commercially. That’s the story of Nihon Home Spun.

Warp threads are set vertically before the textile is woven. Each thread is individually passed through the hole of each wire in a monotonous process.

- ――

- So the war brought this textile out of the home and into commercial production.

- Kikuchi

- Our buyers have also changed with the times. At first we sold to tailors, and then wholesalers. Then an increasing part of our business came from apparel manufacturers. In the ‘80s, designer brands began coming to us. Because there are so few businesses here in Hanamaki, we always went to Tokyo to sell our goods. That left us little time to look into all the brands, so we would always end up going back to the same ones. And every time they would tell us to make something different.

- ――

- I can see that happening. (laughs)

- Kikuchi

- So as we kept making adjustments for these buyers, we ended up with thousands of different designs. Then the brands would debut all over the world and ask us about making fabrics out of particular kinds of thread. At that point, everything was still hand-woven.

There’s a mountain of samples in the Kikuchi plant. There are no designers, so the president, his son (senior managing director), and his daughter work together to make three designs a day, leading to 700 new textiles a year.

- ――

- So you were working by hand until the ‘80s?

- Kikuchi

- No, it was later than that. Hand-weaving means every weaver works a different piece. When we started working with overseas brands, they told us they wanted their products to be consistent without sacrificing the hand-woven look. We bought some machines eventually — that was around 2001 or 2002.

- ――

- So until that recently everything was still hand-woven?

Over 2000 types of yarn are stocked. There’s sheep’s wool, which is used for homespun threads, washi paper dyed with mud, washi shaped like tape, and other unique yarns.

“Why don’t we incorporate quintessentially Japanese materials into our work for foreign brands, like mud-dyed washi paper or indigo dye? We dye in-house. You know how tape has a width to it? We’re the only ones who can weave using the tape-shaped material as a warp thread, but no one would buy it.” (laughs)

- Kikuchi

- Even now, when a small amount is required, it’s faster for us to just weave it by hand. Samples, for example, are all done by hand; when it comes time for mass production we use machines.

- ――

- When you’re making large quantities, is it much faster to use a machine?

- Kikuchi

- If you listen closely, you can hear the rhythmic sound of the machines weaving. In our factory, it’s 60 times a minute. Elsewhere it’s usually 120 to 180.

- ――

- Wow, that’s a third of the speed.

- Kikuchi

- Well, homespun was originally spun and woven by hand. Nowadays hand-spun thread is very rare, but we wanted to preserve the hand-spun feel. The threads are imperfect, and made at uneven thicknesses. That’s why we need to weave at a slower pace than other places do. If we were always aiming for efficiency, we wouldn’t be able to make this kind of textile at all. (laughs)

Everyone in the factory knows how to hand-spin thread.

- ――

- Do you still spin thread by hand?

- Kikuchi

- We’re still able to, of course. Because our name is Hand Spun, we rely on that technique and have every intention of preserving it.

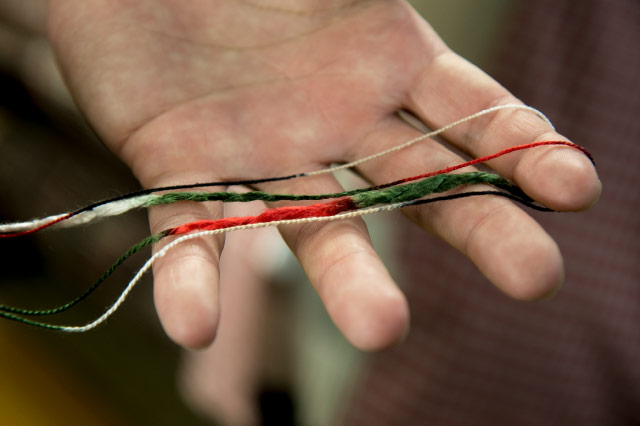

The threads for Saikoshi were individually dyed into various colors. Their thicknesses also vary, as the thick threads don’t contain much color, while the thin threads have been darkly dyed. This produces a complex color scheme.

A pot where threads are dyed. Saikoshi threads were also dyed here.

Because it’s a checkered pattern, the horizontal threads are the same.

Because the threads vary in thickness, they must be woven at a slow pace. This allows plenty of air in and keeps the material soft.

The progress is constantly monitered for loose threads, which are adjusted on the spot.

A finished piece. The threads vary in color and thickness, creating a beautiful tartan design.