3Bishu: A global woven textile production center

At the center of Ichinomiya city in Aichi prefecture, situated among the lush natural resources of the Kiso Three Rivers, is one of the largest woven-textile manufacturing districts in the world, with a reputation that stands up alongside the famous Italian district of Biella. We spoke to Kaichi Shimizu from the textile manufacturer Nakaden Keori about the Bishu region’s rich tradition of woven textile manufacturing, which dates back to over a hundred years ago.

Kaichi Shimizu, director of thread, planning and production management.

- ――

- Bishu fabric is made from sheep’s wool, right?

- Shimizu

- That’s right. In areas around Aichi and Gifu, cotton fabrics used to be bountiful. In fact, in the Meiji period (1868-1912), this area produced more cotton thread than anywhere else in Japan. At that time, wool production systems were still being refined. During the first World War the demand for wool exploded, and the area transformed into a national manufacturing center for wool products. Today there are about 90 textile producers in the region. Nakaden Keori has operated for 57 years, but compared to most of the mills in the Bishu region we’re quite young. Many companies here are over 100 years old.

- ――

- Why did wool production center concentrate in Bishu?

- Shimizu

- The Kiso, the Ibi, and the Nagara — the Kiso Three Rivers — are the biggest reason. But the weather is also important; all year long the humidity is 60 percent, which is ideal for wool production.

- ――

- So the textile industry grew from the water that was available, and the hot and humid weather was ideal for working with wool.

- Shimizu

- Right. There are many steps involved in producing wool textiles. Companies and factories exist here that specialize in each of those steps. For something as simple as spinning wool into thread you’ll find 30 large corporations and 200 mom-and-pop mills.

- ――

- You mean all across Japan?

- Shimizu

- No, just in Bishu!

- ――

- Wow, that many?

- Shimizu

- Of course, it used to be many more than that. About 30 years ago, there were 6000 mills operating to weave the finished threads.

- ――

- 6000!

- Shimizu

- On your way to visit us today, did you see all the sawtooth-shaped buildings?

- ――

- We did! The really unique buildings with jagged roofs.

The “sawtooth” roofs in Ichinomiya face north to take in the morning sun.

- Shimizu

-

Those are mills. A tradition dating back to the first textiles that were made here states that the sunlight is perfect for matching colors between the hours of 10 and 11 AM. So all the mills faced north to take advantage of the morning sun.

Most of them were small, family-owned operations. People called them “Three-Up Shops,” because they were run by three people — Mom, Dad, and Grandma. There are about 350 of those left; that’s 5 percent of what it was 30 years ago.

- ――

- That’s a very steep decline.

- Shimizu

- It is. But even now most domestic wool textiles are produced here in the Bishu region. Some statistics put the number as high as 80 percent. This is a bit of a tangent, but it’s not entirely unrelated — the Ichinomiya area also has Japan’s highest concentration of coffee shops.

- ――

- Coffee shops!

- Shimizu

-

Back then, the Dad of each of those 6000 “Three-Up Shops” would wake up at 6 AM and set the threads on the machines, which were Mom’s job to weave. While Mom was weaving, Dad would go down to the coffee shop. Because Mom was too busy working to make breakfast, Dad would ask the owner for a bite to eat. The popular morning “meal sets” of this whole part of the country got their start in that way: For the price of the coffee they would also get bread, salad, and fruit.

You might wonder how those coffee shops ever made any money. But the Dads loved skipping out of work and heading over there — they’d do it three or four times a day! At least that’s the origin story everyone tells around here.

- ――

- That’s interesting. (laughs) So the coffee shops grew from the needs of the mill Dads.

- Shimizu

- That kind of derailed the topic, but I wanted to illustrate just how many mills there were for just a single process of weaving. Our company has both a weaving machine and a circular knitting machine, which is an incredibly rare combination.

- ――

- So there are many kinds of specialists who each handle a particular step in the process.

- Shimizu

-

That’s right. There’s a mending shop, whose sole purpose is repairing cloth when a thread is snapped or soiled in production. The raw cloth, which is referred to as “gray goods,” is taken there to be fixed.

At the next step in the process, the finishing shop, the cloth is washed, kneaded, and treated. If any loose threads are found in the finished product, it’s returned to the mending shop. Even if something is only discovered after it’s delivered to the customer, the repairs are made at the mending shop.

This mending service isn’t really common outside of the Bishu area. Compared to other natural and synthetic fibers, wool threads snap more easily during the weaving process. Wool thread is also more expensive than cotton, so it makes more sense to mend imperfect material.

- ――

- Sounds like it’s a step unique to Bishu.

- Shimizu

- The finishing shop is also unique to Bishu. Wool shrinks, so if something contains more than 20 percent wool, other areas have a difficult time working with the final product. You can only find the necessary technique in an area like this. In fact, even in Bishu there are no more than 10 places that can do it, and each of them works in a different specialty — men’s or women’s clothing, knitted materials, fields like that. That’s how this region grew to involve so many people working in each process.

- ――

- That’s amazing

- Shimizu

-

There are so many businesses that specialize in the thread-dyeing process, for instance, that it would take you half a day just to see them all. At the finishing shop, there are 30 or 40 kinds of machines, and each one does only one part of the process. Sometimes newly woven cloth can undergo an unrecognizable transformation.

In the past, there was a saying: “Kids who slack off end up at the thread-dyeing factory; kids who do all right end up at the mill; kids who study hard and do well end up at the finishing shop.” So much more went on at the finishing shop, with all its chemicals and machines, than it did anywhere else. But at some point that old saying flipped. Finishing shops became like subcontractors to slightly dishonest mills. But more recently, because they’re decreasing in number, the value of a good finishing shop is going back up.

- ――

-

That’s a classic story for a major industrial region. (laughs)

Wool has a strong association with fall and winter wear. Is wool production also seasonal?

- Shimizu

-

Absolutely. Woven garments are worn most often in fall and winter, so we’ve been working to create spring and summer items that incorporate synthetic woven blends, like polyester, nylon, and rayon. After all, we already have the basic technology from back when the mills in this area produced cotton fabrics.

Today wool is just 1.2% of the textile market, so I’d be lying if I told you this wasn’t a tough industry. Even the number of sheep here has declined. There used to be 200 million sheep; now there are only 75 million. But I want to continue making products that exemplify Bishu, Japan’s finest manufacturing region. It’s not just about producing the finished product, but about relying on finishing shops and working through the complicated processes necessary to meet the challenge and produce new materials. My goal is to bring new value to the fabrics we create.

This knit textile was processed through a series of complicated techniques at the finishing shop.

A step called warping. This factory has incorporated a great deal of machinery, but this particular step cannot be automated; the threads are still tied by hand.

The second stage of warping involves winding threads. This is a crucial part of the process: If this goes well, the weaving will, too.

This accumulator evens out the tightness of the threads. The machine takes threads made from wool, polyester, or other material and makes them all even. When these machines were introduced to this area, they were so rare that only three existed in Japan, including the textile museum.

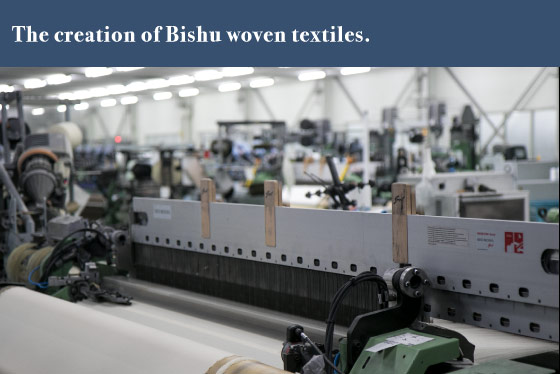

A stretch of looms. Today the weaving process is almost entirely automated.

A circular knitting machine produces knitted goods.

A fabric showroom that displays the latest creations and conducts promotional events for the Bishu area, such as the “Tweed Run.”